Bookneedle 004 / The Visible Soul

“I thought of telling the prophet that Art had a soul, but that man had not.”

Book: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

This BookNeedle comes in the penultimate chapter of the novel, chapter 19 and is spoken by the character Lord Henry Wotton, who is talking with the main character Dorian. Dorian confesses that he is changing his life in order to be good. Henry does not want Dorian to change. During their conversation, Henry quotes a street-preacher he heard while walking through a park: “what does it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose . . . His own soul?” Dorian wonders why Henry asked him that only to find out that Henry thought Dorian would know the answer. The “street-preacher” is the same person Henry then ponders whether to tell “the prophet that Art had a soul, but that man had not.”

Soul, Art, and Man

Distancing the soul from man and into art as told to a prophet proposes first, that this is a statement of truth that should be recognized by a prophet as coming from a god, second, that there is a soul, third, that art reflects in man what man is without, and fourth, that with knowledge, the essence of a soul can be discovered. A definition of the “soul,” however, immediately connects it with man - “the essence of the individual.” (Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, Oxford Classical Dictionary). So, to distance man from the soul yet having that same “man” be able to identify the essence of a soul in god-like fashion, inevitably gives art the window into self-reflection, where the frame is defined by perspective and at the same time includes your own reflection. The soul, like art, itself is thus separate from the body:

“So that this I, that is to say the soul by which I am what I am, is entirely distinct from the body, is even easier to know than the body, and furthermore would not stop being what it is, even if the body did not exist.”

(Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy)

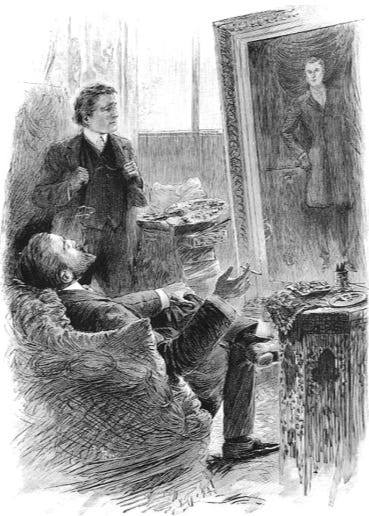

The painter Basil Hallward and the aristocrat Lord Henry Wotton observe the picture of Dorian Gray.

Soul as Intermediary

This BookNeedle proposes that the soul is the intermediary between art and the reflection of the soul in man, discoverable through the utility of man, the bodily senses. “The simple truth is that your senses are the chief part of you: you think with them.” (Ronald Fraser, Flower Phantoms). In this context, the sentient sense comes from the eye. Aristotle proclaimed that “[t]he soul never thinks without a mental image” (Aristotle, On the Soul) and Leonardo da Vinci submitted that “[t]he eye, which is said to be the window of the soul, is the principal means by which the brain’s sensory receptor may fully and magnificently contemplate the infinite works of nature.” (Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Ashburnham).

Why Art?

Art can express the soul because within the capacity to experience, there is “a ‘gap’ between self and the world, between stimulus and response,” and it is within that space that art resides. (Rollo May, ‘Freedom and Responsibility Re-Examined’). Art is there to “awaken in us the emotion corresponding to the theme they [artists] have discovered, of showing us what richness, what variety lies hidden, unknown to us, in that vast, unfathomed and forbidding night of our soul which we take to be an impenetrable void.” (Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time). It is not logic, but that something else that art gives, for “[r]eason’s wings are short.” (Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy).

The trick of art in disclosing the soul is in establishing a world recognizably beyond reason in order to show that which is beyond reason.

Art itself is a visual error, one depicting a truth that is not actually true. Consider the story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius as recorded by the Roman philosopher Gaius Plinius Secundus, known as Pliny the Elder. Zeux and Parrhasius were rival painters who decided to challenge one another to determine who had the better skills. In the agreed to competition, each artist was to execute a wall painting and judge for themselves. When finished, Zeuxis revealed his painting of a bunch of grapes that were depicted with such lifelike qualities that birds attempted to eat the fruit. Feeling confident in his victory, Zeuxis asked Parrhasius to unveil his painting. Parrhasius refused, explaining that the veil itself was in fact his painting. Zeuxis acknowledged his defeat, stating “Whereas he had deceived birds Parrhasius had deceived him, an artist.” (Pliny, Natural History).

What the story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius suggests is that art, itself unreal in the sense of depicting something other than the arrangement of paint, is a corridor for the mind to the soul. As the birds believed in the reality of the fruit, the audience believed in the reality of the curtain. But there is something more that the audience sees when they realize the illusion, that truth can be found beyond reality and beyond the senses. For experience of the senses is not real, but a memory of the past. “By the time you think the moment occurs, it’s already long gone. To synchronize the incoming information from the senses, the cost is that our conscious awareness lags behind the physical world.” (Annaka Harris, Conscious). Memory is the adaptive force of the soul.

Art is Soul

While the human senses may take in the essence of art, the fact that the soul, like art, is timeless and undefined, makes understanding it entirely through the human senses impossible. It is unrelentingly present, confronting you with its existence, instigating you to understand, a heroic endeavor thrust upon the mind “to prove my soul.” (Robert Browning, ‘Paracelsus’). This heroism originates in ambiguity in the same way that “[a]rt enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.” (Thomas Merton, No Man is an Island). In other words, art is the basis for reflection, a reflection that changes upon changing perspectives. “[A]rt is a perpetual representation, the fact represented must be viewed by the painter through a medium, which is nothing less than his own soul, which is his highest conception, the mainspring of his intellectual existence.” (Ernest Chesneau, English Painting).

The purpose is to discover, “where the miraculous finds its last refuge in the soul of the human being represented in the work of art.” (Ken Wilder, Beholding). This representation is a reflection, which is brought to the art: “It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.” (Oscar Wilde, ‘Letter to Editor of the Scots Observer,’ July 23, 1890). As explained by Wilde: “Each man sees his own sin in Dorian Gray. What Dorian Gray’s sins are no one knows. He who finds them has brought them.” (Oscar Wilde, ‘To the Editor of the Scots Observer,’ July 9, 1890). Thus peering into the soul can be a dangerous endeavor: “when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil). Similarly, the character Kurtz in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness expresses his sins in the reader. These sins are never fully discussed in the novel, but they are there when you read it. “That is why Marlow can tell his story as he does in Conrad's novel. He has no need to count up the crimes Kurtz committed. He has no need to describe them. He has no need to produce evidence. For no one doubted it.” (Sven Lindqvist, Exterminate All the Brutes). Art provides us with this abyss for which we can discover our soul.

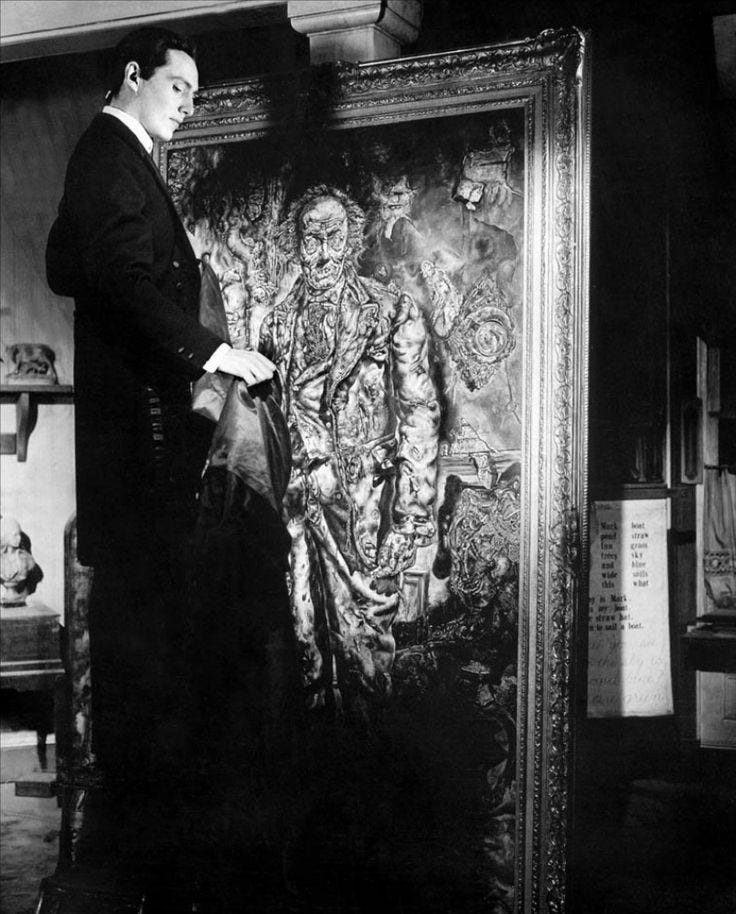

The Picture of Dorian Gray. Directed by Albert Lewin, MGM, 1945.

The mind converses with art both consciously and unconsciously, reaching the depths of memory and experience. An abyss that allows all comers into self-received transcendence in and out of thought. An “understand[ing] in a different way,” as Carson Mcather writes in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, describing what it is like for the characters to converse with a deaf mute is instructive:

“All was quiet. It was like they waited to tell each other things that had never been told before. What she had to say was terrible and afraid. But what he would tell her was so true that it would make everything all right. Maybe it was a thing that could not be spoken with words or writing. Maybe he would have to let her understand this in a different way. That was the feeling she had with him.”

This conversation with the deaf mute is like confronting art, you don’t know why, but there is understanding, it tells you things in “a different way,” one that you get every so often: “a man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” (Albert Camus, “The Wrong Side and the Right Side,” Lyrical and Critical Essays). Art expresses a universe that is open to discovery. “It was as though he had become aware of the soul of the universe and were compelled to express it. Though these pictures confused and puzzled me, I could not be unmoved by the emotion that was patent in them.” (W. Somerset Maugham, The Moon and Sixpence).

Without reason or purpose, we look upon art as an unknown until it becomes our personal known. For “[t]he clay of the human soul is entirely unworked, unsculptured, its feelings still crude and boorish, unable to divine anything with clarity or certainty.” (Nikos Kazantzakis, Zobra the Greek). That personal known is the soul divined through art.

Books Mentioned

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy. Trans. James Innes Minchin. Forgotten Books, 2018.

Aristotle. Aristotle: On the Soul. Parva Naturalia. On Breath. Trans. W.S. Hett. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2000.

Browning, Robert. Paracelsus. New York, Clean Bright Classics, 2017.

Camus, Albert. Lyrical and Critical Essays. New York, Vintage Books, 1968.

Chesneau, Ernest. English Painting. New York, Parkstone Press International, 2015.

Da Vinci, Leonardo. Codex Ashburnham. 2:19r-v., l’Institut de France, Paris, 1530.

Descartes, Rene. Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. Trans. Ian Johnston. Broadview Press, Ontario, 2020.

Fraser, Ronald. Flower Phantoms. Kansas City, Valancourt Books, 2013.

Harris, Annaka. Conscious. New York, HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2019.

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3d ed. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996.

Kazantzakis, Nikos. Zorba the Greek. New York, Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1952.

Lindqvist, Sven. Exterminate All the Brutes. New York, The New York Press, 1996.

Lloyd-Jones, Esther and Esther M. Westervelt. Behavioral Science and Guidance: Proposals and Perspectives. ‘Freedom and Responsibility Re-Examined’ by Rollo May, New York, Bureau of Publications, 1963.

Maugham, W. Somerset. The Moon and Sixpence. New York, Penguin Group, 2005.

McCullers, Carson. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Boston, First Mariner Books, 2000.

Merton, Thomas. No Man is an Island. San Diego, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1955.

Neitzsche, Friedrich and R. J. Hollingdale. Beyond Good and Evil. London, Penguin Books, 2003.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. London, Penguin Books, 2004.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time. New York, Modern Library, 1981.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York, Random House: Modern Library, 2004.

Wilde, Oscar, Merlin Holland, and Rupert Hart-Davis. The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. “Letter to the Editor of the St. Jame’s Gazette, June 26, 1890.” London: Fourth Estate, 2000.

Wilder, Ken. Beholding. London, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.